I’ll be honest to say we had absolutely no clue about what makes up a building superstructure or sub structure when we started. All we knew when we started talking to friends and family was we wanted an eco house. As it turns out, that means different things to different folks.

We did buy a few books to educate us on what it means and what the current standards look like. It turns out there is no one definition on what an eco-home means. According to Christopher Day in his book the Eco-Home Design Guide, it’s safer to focus on ecological stability.

Ecological stability which includes climate stability as well is all about preserving or recycling key resources (e.g. water, nutrients, sometimes feedstocks). It’s essentially the maintenance of a self-regulating ecology, reducing pollution and preserving biodiversity. More importantly it’s about living in harmony with nature.

Ok, so we can get purist about it or pragmatic. But there are key principles we wanted to adopt. They include thermal performance to reduce more impact on climate change, sustainable energy source and use including future proof design within reason and cost.

So we decided on some key design decisions, we wanted a life time cost saving on energy, e.g. generate our own electricity from solar where possible,

Climate protection with an airtight and carbon-negative design. Well being from a sensory perspective and environmental impact reduction.

On that basis, we engaged with Max Fordham, a sustainable building engineering consultancy to design the services and mechanical engineering for us. The first step was to answer a series of question in a matrix covering aspiration, mechanical, electrical, communication & entertainment systems, security systems, external services and utilities.

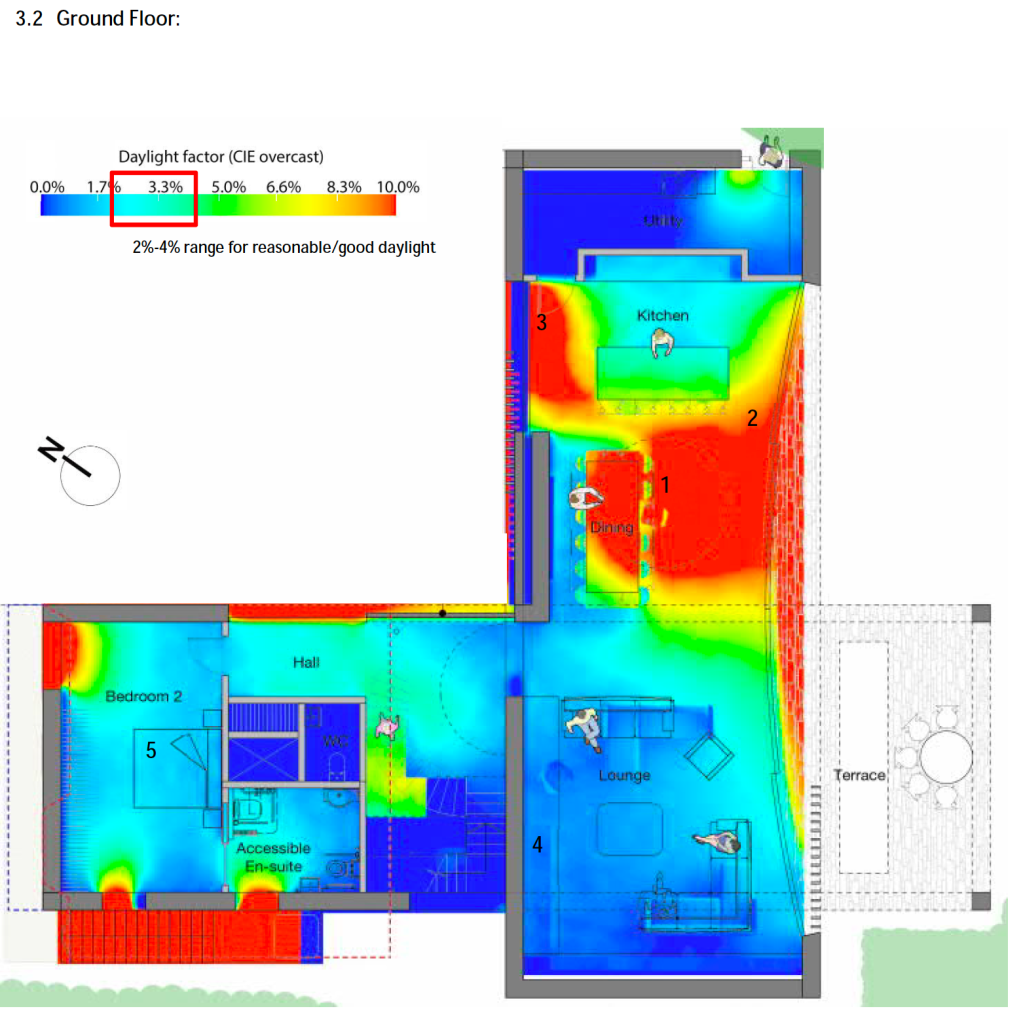

Once we completed this, we did a daylight analysis using the first sketches produced by our architect. This analysis enabled us to determine how much direct sunlight each room will receive over the course of a day.

The day light factor for each space was then derived. A red Indicates areas receiving very high levels of cumulative direct solar gain. This then needs to be mitigated by altering the design for example.

In the example above for the ground floor, We discovered, the following.

1 Rooflight provides very high DF. Consider reducing size to limit winter heat loss and summer overheating. Target rooflight area to be 10% of

floor area

2 Window provides high DF to kitchen/dining area. Consider movable external shading to reduce summer overheating risk. Good DF in lounge, good balcony shading

3 Good daylight in kitchen from rooflight and south facing window. Consider reducing glazing area to north to reduce winter heat loss

4 Consider adding an internal window to the staircase case to increase DF at the rear of the lounge.

5 Good DF in bedroom 2, en-suite and hall.

Energy Demand

In order to assess the feasibility of “energy positive” an analysis of the energy demands of the occupied building has been completed. The “Passivhaus Planning Package (PHPP)” method was applied using preliminary design information to estimate the heating demands for the building as well as to indicate how much electricity the building may need over the course of a typical year. This should be considered a low resolution analysis, suitable for preliminary discussions, preceding a more intensive analysis such as dynamic thermal modelling which will be performed to size plant and equipment.

The diagram below indicates a hierarchy of design, loosely based on the London Plan, which can be applied to achieve an energy-positive building.

The preliminary analysis gives an indication of the relative proportion of the building’s energy demand associated with heating, lighting, providing hot water, and other essential activities such as cooking.

This equates to a building electrical demand of 39.3 kWh/mÇ per annum, which is 25% lower than what might be expected for a newly built house in the UK.

The following sections detail steps that can be taken following the hierarchy of design in order to achieve the goal of being energy-positive.

Be Lean (Winter)

Target to be “energy-positive”

“Be Lean”

Reduce building energy losses to reduce heating demand

Use as much “free” energy from solar and internal gains as possible

Reducing energy losses

1 High quality insulation, target maximum U values of 0.1 W/m²K for walls, roof,

2 High quality glazing, target maximum U value of 0.8 W/m²K for window installation,

3 Air tight construction, maximum 0.6 air changes per hour by infiltration @50 Pa,

4 Minimise thermal bridges in construction,

Using “free heat” from solar and internal gains

5 Use free heat from internal gains to heat space, allowing the ventilation system to redistribute from warmer areas to colder areas.

6 Size windows to balance benefits of solar heat in winter and daylighting against overheating risk in summer.

Be Lean (Summer)

Target to be “energy-positive”

“Be Lean” (Summer)

· Minimise internal heat gain in summer to keep the building cool, avoiding the need for electrical cooling (A/C).

· Perform overheating analysis to ensure building can be kept within a comfortable temperature range.

Reducing internal gains

1 High quality insulation, target U values of 0.1 W/m²K max for walls, floor and roof.

2 Solar control glazing in some areas

3 Internal blinds – ideally reflective on external side

4 Appropriate thermal mass in construction – thermal mass absorbs excess heat and releases it slowly stabilising internal peak temperatures on hot days

5 Temporary external solar shading – most effective way to reduce overheating

Be Clean

Target to be “energy-positive”

“Be Clean”

Use efficient appliances to reduce energy demand further

1 Heat recovery mechanical ventilation (MVHR)

2 LED lighting with daylight dimming

3 Technology to use hot water more efficiently – e.g. aerating shower

4 Heat pump(s) to provide heating and domestic hot water

5 Energy storage – Tesla Powerwall

6 High efficiency inverter/ control for energy storage

Be Green

Target to be “energy positive”

“Be Green”

Effective use of renewable technology

1 Maximise PV capacity on south facing roof and on field shelter (and/or elsewhere if necessary)

2 Greywater harvesting – store sink/shower drain water for irrigation/ toilet flushing

3 Green roof/ rainwater run off harvesting – use for irrigation

4 Laundry drainage harvesting – use for irrigation/ toilet flushing

5 Demand management – manage electric loads e.g. car charging, laundry to coincide with PV availability to avoid battery charge/discharge losses.

Be Energy Positive

Achieving “Energy Positive)

(-£ indicates an associated initial cost saving, +£, +££ and +£££ respectively indicate low, medium, and high associated initial costs)

1 Reduce appliance demand by 5% by drying clothes outside instead of tumble drying(-£)

2 Reduce window heat loss (e.g. reduce NE & SW window sizes and/or use insulated shutters or other insulating measure in winter) (-£ to +£)

3 Reduce domestic hot water demand to 25l/person per day with eco-conscious usage and water efficient appliances such as atomising showers. (+£)

4 Improve wall insulation from U = 0.1W/m.K to 0.08W/m.K (+££)

5 Reduce thermal bridges by 50% from base case to reduce heating demand. (+££)

6 High quality heat pump installation (SCOP 4 vs SCOP 2.5) (+££)

7 Increase air tightness from 0.6 ACH to 0.2 ACH to reduce heating demand (+££).

Clearly, there is a lot to take in with all the above, but the key point for us to build a house which aspires to tick the boxes of the Passivhaus standard, we need to ensure things like airtightness and heat-loss including a mechanical heating recovery and ventilation system are part of the design.

What is a Passivhaus?

According to the HouseBuilder’s Bible Twelfth Edition written by Mark Brinkley, A Passivhaus is a demanding technical standard which more or less guarantees not only very low energy consumption but very high building standards. It just concentrates on energy use and comfort. If people want to add water efficiency measures or renewable energy devices, that is up to them but it’s not part of the classic Passivhaus standard.

The three pillars of Passivhaus are demanding insulation levels, close attention to the details of achieving airtightness and a reliance on mechanical ventilation with a heat recovery system.

A Passivhaus is characterised by almost always triple glazing and very little in the way of space heating. They aim to be warm and comfortable all year round with an absolute minimum of space heating required. However, it’s not dogmatic on insisting on any of the other ecological measures on can adopt to build a sustainable home.

For the purpose of our design, we did an assessment using the Passivhaus Planning Package (PHPP) and our initial score of our design is in the image below.

The building was assumed to be well insulated with relatively low thermal bridging and a medium thermal mass construction in order to reduce the risk of overheating in summer.

The following U values were applied to the model:

· Walls – 0.1 W/m.K

· Roof – 0.08 W/m.K

· Floor – 0.1 W/m.K

It was assumed that the building would have an air change rate of 0.6 air changes per hour, in line with what is expected of a Passive House. It is important that the building is as air tight as possible in order to reduce winter heating demand as well as to keep the house passively cool in summer.

A significant number of potential thermal bridges have been taken into consideration and included in the model, resulting in a considerable amount of indicated heat loss (see section 4.6). Elements such as façade fixings, balconies, internal rainwater pipes, and certain structural junctions/elements contribute significantly to thermal bridge losses and

as such will require careful detailing if unavoidable.

Final Considerations

Given the scale of building and sustainability engineering. We also made some key design decisions, we decided to go with Solar roof tiles vs. solar panels to reduce the impact on aestethics. We aspired to use the Tesla Solar Tiles but didn’t have any guarantee they will be available when we need them so we opted for SolGB PV Slates. We also decided to go with a Structural Insulated Panel (SIP) and Steel construction method which I’ll cover in the structural engineering section.

In addition to the above, we’re going with a ground source heat pump and Tesla Powerwalls as Home Batteries. As an aside, the government has removed the old subsidy for renewable energy generation in the UK and moved to the Smart Export Guarantee Scheme this year. The implication is you should save whatever excess energy you’re using in an Inverter so you can use it later e.g. to charge electric vehicles. Only the excess of that should go back to the grid as the money you get back is not worthwhile if you’ve not thought through all these.

The government is also introducing VAT in October this year. Therefore, if you want to save money you may need to do it now or never. Unless a new government comes and changes this.

The Renewable Heat Incentive (the RHI) is a payment system in England, Scotland and Wales, for the generation of heat from renewable energy sources. Introduced on 28 November 2011, the RHI replaces the Low Carbon Building Programme, which closed in 2010.

The RHI operates in a similar manner to the Feed-in Tariff system, and was introduced through the same legislation – the Energy Act 2008.[1] In the first phase of the RHI cash payments are paid to owners who install renewable heat generation equipment in non-domestic buildings: Commercial RHI.

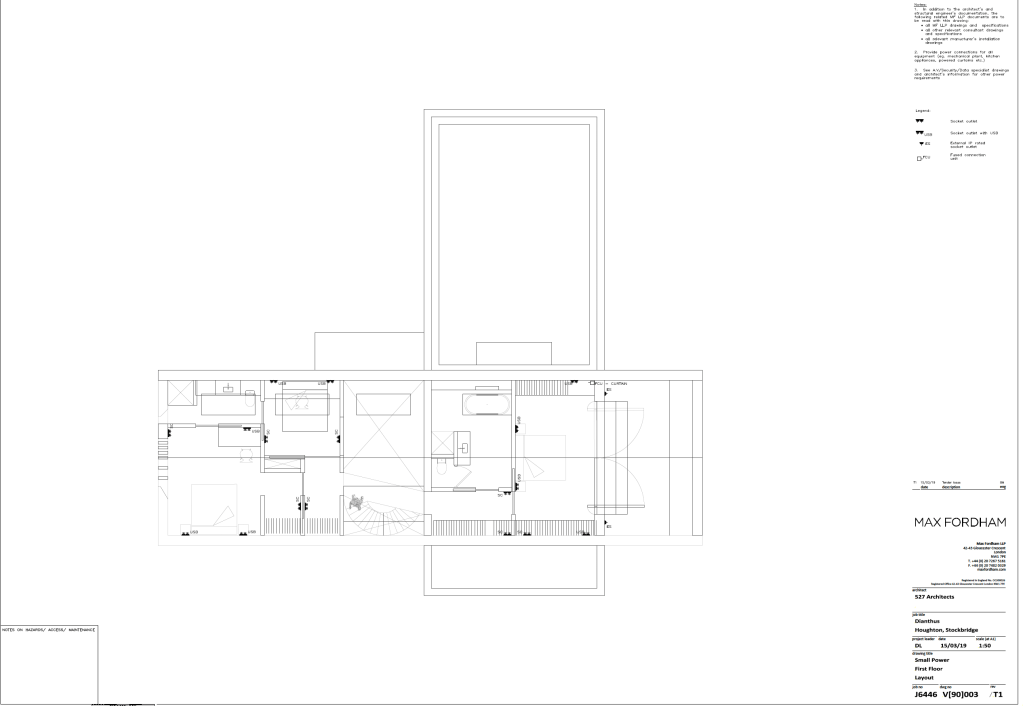

A few best practices we learnt from the Barkers, Specify all your sockets up front including think about where you’ll plug vacuum cleaners and Christmas trees. We marked up each floor obsessively. One of the other things we also did was specify double banks of sockets with USB standards, of course you can update to USB-C later. We also ensure the cabling was to CAT6A Standard or greater because of the bandwidth.

Finally, we put in a few EV charging points given EVs are about to take off in the next few years and we’re already driving an EV anyway. So we put in three points for EV on the plan. See the main feature image above.

5 thoughts on “Building, Mechanical and Sustainability Engineering”